Social Credit on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Social credit is a distributive philosophy of

In January 1919, "A Mechanical View of Economics" by C. H. Douglas was the first article to be published in the magazine ''New Age'', edited by

In January 1919, "A Mechanical View of Economics" by C. H. Douglas was the first article to be published in the magazine ''New Age'', edited by

C. H. Douglas was a

C. H. Douglas was a

C.H. Douglas's book ''Economic Democracy'' at American Libraries

C.H. Douglas's book ''Credit-Power and Democracy'' at American Libraries

C.H. Douglas's book ''The Control and Distribution of Production'' at American Libraries

C.H. Douglas's book "The Monopoly of Credit"

C.H. Douglas's work "The Douglas Theory, A Reply to Mr. J.A. Hobson" at American Libraries

C.H. Douglas's work, "These Present Discontents" at American Libraries

Hilderic Cousens, "A New Policy for Labour; an essay on the relevance of credit control" at American Libraries

Bryan Monahan, "Introduction to Social Credit"

M. Gordon-Cumming, "Money in Industry"

– online library

The Green Shirt Movement for Social Credit Social Credit Party of Great Britain archives

Social Credit School of Studies

Social Credit Secretariat

Social Credit Website

Clifford Hugh Douglas Institute

Catalogue of the social credit publications collection

held at the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick {{Authority control Social credit, Schools of economic thought Monetary economics Political philosophy

political economy

Political economy is the study of how Macroeconomics, economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and Economy, national economies) and Politics, political systems (e.g. law, Institution, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied ph ...

developed by C. H. Douglas. Douglas attributed economic downturns to discrepancies between the cost of goods and the compensation of the workers who made them. To combat what he saw as a chronic deficiency of purchasing power

Purchasing power is the amount of goods and services that can be purchased with a unit of currency. For example, if one had taken one unit of currency to a store in the 1950s, it would have been possible to buy a greater number of items than would ...

in the economy, Douglas prescribed government intervention in the form of the issuance of debt free money directly to consumers or producers (if they sold their product below cost to consumers) in order to combat such discrepancy.

In defence of his ideas, Douglas wrote that "Systems were made for men, and not men for systems, and the interest of man which is self-development

Self-help or self-improvement is a self-guided improvement''APA Dictionary of Physicology'', 1st ed., Gary R. VandenBos, ed., Washington: American Psychological Association, 2007.—economically, intellectually, or emotionally—often with a subst ...

, is above all systems, whether theological, political or economic." Douglas said that Social Crediters want to build a new civilization based upon " absolute economic security" for the individual, where "they shall sit every man under his vine and under his fig tree

''Ficus'' ( or ) is a genus of about 850 species of woody trees, shrubs, vines, epiphytes and hemiepiphytes in the family Moraceae. Collectively known as fig trees or figs, they are native throughout the tropics with a few species extending ...

; and none shall make them afraid." In his words, "what we really demand of existence is not that we shall be put into somebody else's Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', describing a fictional ...

, but we shall be put in a position to construct a Utopia of our own."

The idea of social credit attracted considerable interest in the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

, with the Alberta Social Credit Party

Alberta Social Credit was a provincial political party in Alberta, Canada, that was founded on social credit monetary policy put forward by Clifford Hugh Douglas and on conservative Christian social values. The Canadian social credit movement w ...

briefly distributing "prosperity certificates" to the Albertan populace. However, Douglas opposed the distribution of prosperity certificates which were based upon the theories of Silvio Gesell. Douglas' theory of social credit has been disputed and rejected by most economists and bankers. Prominent economist John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

references Douglas' ideas in his book ''The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money

''The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money'' is a book by English economist John Maynard Keynes published in February 1936. It caused a profound shift in economic thought, giving macroeconomics a central place in economic theory and ...

,'' but instead poses the principle of effective demand The Principle of Effective Demand is the title of chapter 3 of John Maynard Keynes's book ''The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.'' The principle presented in that chapter is that the aggregate demand function and the aggregate supp ...

to explain differences in output and consumption.

Economic theory

Factors of production and value

Douglas disagreed withclassical economists

Classical economics, classical political economy, or Smithian economics is a school of thought in political economy that flourished, primarily in Britain, in the late 18th and early-to-mid 19th century. Its main thinkers are held to be Adam Smith ...

who recognised only three factors of production

In economics, factors of production, resources, or inputs are what is used in the production process to produce output—that is, goods and services. The utilized amounts of the various inputs determine the quantity of output according to the rel ...

: land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of the planet Earth that is not submerged by the ocean or other bodies of water. It makes up 29% of Earth's surface and includes the continents and various islan ...

, labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

and capital. While Douglas did not deny the role of these factors in production, he considered the " cultural inheritance of society" as the primary factor. He defined cultural inheritance as the knowledge, techniques and processes that have accrued to us incrementally from the origins of civilization (i.e. progress

Progress is the movement towards a refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. In the context of progressivism, it refers to the proposition that advancements in technology, science, and social organization have resulted, and by extension wi ...

). Consequently, mankind does not have to keep "reinventing the wheel

To reinvent the wheel is to attempt to duplicate—most likely with inferior results—a basic method that has already previously been created or optimized by others.

The inspiration for this idiomatic metaphor is that the wheel is an ancient ar ...

". "We are merely the administrators of that cultural inheritance, and to that extent the cultural inheritance is the property of all of us, without exception." Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

, David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British Political economy, political economist. He was one of the most influential of the Classical economics, classical economists along with Thomas Robert Malthus, Thomas Malthus, Ad ...

and Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

claimed that labour creates all value. While Douglas did not deny that all costs ultimately relate to labour charges of some sort (past or present), he denied that the present labour of the world creates all wealth. Douglas carefully distinguished between value

Value or values may refer to:

Ethics and social

* Value (ethics) wherein said concept may be construed as treating actions themselves as abstract objects, associating value to them

** Values (Western philosophy) expands the notion of value beyo ...

, costs

In production, research, retail, and accounting, a cost is the value of money that has been used up to produce something or deliver a service, and hence is not available for use anymore. In business, the cost may be one of acquisition, in which ...

and price

A price is the (usually not negative) quantity of payment or compensation given by one party to another in return for goods or services. In some situations, the price of production has a different name. If the product is a "good" in the c ...

s. He claimed that one of the factors resulting in a misdirection of thought in terms of the nature and function of money was economists' near-obsession about values and their relation to prices and incomes. While Douglas recognized "value in use" as a legitimate theory of values, he also considered values as subjective and not capable of being measured in an objective manner. Thus he rejected the idea of the role of money as a standard, or measure, of value. Douglas believed that money should act as a medium of communication by which consumers direct the distribution of production.

Economic sabotage

Closely associated with the concept of cultural inheritance as a factor of production is the social credit theory of economic sabotage. While Douglas believed the cultural heritage factor of production is primary in increasing wealth, he also believed that economic sabotage is the primary factor decreasing it. The word wealth derives from theOld English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

word , or "well-being", and Douglas believed that all production should increase personal well-being. Therefore, production that does not directly increase personal well-being is waste, or economic sabotage.

The economic effect of charging all the waste in industry to the consumer so curtails his purchasing power that an increasing percentage of the product of industry must be exported. The effect of this on the worker is that he has to do many times the amount of work which should be necessary to keep him in the highest standard of living, as a result of an artificial inducement to produce things he does not want, which he cannot buy, and which are of no use to the attainment of his internal standard of well-being.By modern methods of accounting, the consumer is forced to pay for all the costs of production, including waste. The economic effect of charging the consumer with all waste in industry is that the consumer is forced to do much more work than is necessary. Douglas believed that wasted effort could be directly linked to confusion in regard to the purpose of the economic system, and the belief that the economic system exists to provide employment in order to distribute goods and services.

But it may be advisable to glance at some of the proximate causes operating to reduce the return for effort; and to realise the origin of most of the specific instances, it must be borne in mind that the existing economic system distributes goods and services through the same agency which induces goods and services, i.e., payment for work in progress. In other words, if production stops, distribution stops, and, as a consequence, a clear incentive exists to produce useless or superfluous articles in order that useful commodities already existing may be distributed. This perfectly simple reason is the explanation of the increasing necessity of what has come to be called economic sabotage; the colossal waste of effort which goes on in every walk of life quite unobserved by the majority of people because they are so familiar with it; a waste which yet so over-taxed the ingenuity of society to extend it that the climax of war only occurred in the moment when a culminating exhibition of organised sabotage was necessary to preserve the system from spontaneous combustion.

Purpose of an economy

Douglas claimed there were three possible policy alternatives with respect to the economic system:1. The first of these is that it is a disguised Government, of which the primary, though admittedly not the only, object is to impose upon the world a system of thought and action. 2. The second alternative has a certain similarity to the first, but is simpler. It assumes that the primary objective of the industrial system is the provision of employment. 3. And the third, which is essentially simpler still, in fact, so simple that it appears entirely unintelligible to the majority, is that the object of the industrial system is merely to provide goods and services.Douglas believed that it was the third policy alternative upon which an economic system should be based, but confusion of thought has allowed the industrial system to be governed by the first two objectives. If the purpose of our economic system is to deliver the maximum amount of goods and services with the least amount of effort, then the ability to deliver goods and services with the least amount of employment is actually desirable. Douglas proposed that unemployment is a logical consequence of machines replacing labour in the productive process, and any attempt to reverse this process through policies designed to attain full employment directly sabotages our cultural inheritance. Douglas also believed that the people displaced from the industrial system through the process of mechanization should still have the ability to consume the fruits of the system, because he suggested that we are all inheritors of the cultural inheritance, and his proposal for a national dividend is directly related to this belief.

The creditary nature of money

Douglas criticized classical economics because many of the theories are based upon abarter economy

In trade, barter (derived from ''baretor'') is a system of exchange in which participants in a transaction directly exchange goods or services for other goods or services without using a medium of exchange, such as money. Economists distingu ...

, whereas the modern economy is a monetary one. Initially, money originated from the productive system, when cattle owners punched leather discs which represented a head of cattle. These discs could then be exchanged for corn, and the corn producers could then exchange the disc for a head of cattle at a later date. The word "pecuniary" comes from the Latin , originally and literally meaning "cattle" (related to , meaning "beast"). Today, the productive system and the monetary system are two separate entities. Douglas demonstrated that loans create deposits

A deposit account is a bank account maintained by a financial institution in which a customer can deposit and withdraw money. Deposit accounts can be savings accounts, Transaction account#Current accounts, current accounts or any of several othe ...

, and presented mathematical proof

A mathematical proof is an inferential argument for a mathematical statement, showing that the stated assumptions logically guarantee the conclusion. The argument may use other previously established statements, such as theorems; but every proo ...

in his book ''Social Credit.'' Bank credit comprises the vast majority of money, and is created every time a bank makes a loan. Douglas was also one of the first to understand the creditary nature of money. The word credit

Credit (from Latin verb ''credit'', meaning "one believes") is the trust which allows one party to provide money or resources to another party wherein the second party does not reimburse the first party immediately (thereby generating a debt) ...

derives from the Latin , meaning "to believe". "The essential quality of money, therefore, is that a man shall believe that he can get what he wants by the aid of it."

According to economists, money is a medium of exchange

In economics, a medium of exchange is any item that is widely acceptable in exchange for goods and services. In modern economies, the most commonly used medium of exchange is currency.

The origin of "mediums of exchange" in human societies is ass ...

. Douglas argued that this may have once been the case when the majority of wealth was produced by individuals who subsequently exchanged it with each other. But in modern economies, division of labour splits production into multiple processes, and wealth is produced by people working in association with each other. For instance, an automobile worker does not produce any wealth (i.e., the automobile) by himself, but only in conjunction with other auto workers, the producers of roads, gasoline, insurance, etc.

In this opinion, wealth is a pool upon which people can draw, and money becomes a ticketing system. The efficiency gained by individuals cooperating in the productive process was named by Douglas as the "unearned increment Unearned increment is an increase in the value of land or any property without expenditure of any kind on the part of the proprietor; it is an early statement of the notion of unearned income. It was coined by John Stuart Mill, who proposed taxing ...

of association" – historic accumulations of which constitute what Douglas called the cultural heritage. The means of drawing upon this pool is money distributed by the banking system.

Douglas believed that money should not be regarded as a commodity but rather as a ticket, a means of distribution of production. "There are two sides to this question of a ticket representing something that we can call, if we like, a value. There is the ticket itself – the money which forms the thing we call 'effective demand

In economics, effective demand (ED) in a market is the demand for a product or service which occurs when purchasers are constrained in a different market. It contrasts with notional demand, which is the demand that occurs when purchasers are not ...

' – and there is something we call a price opposite to it." Money is effective demand, and the means of reclaiming that money are prices and taxes. As real capital replaces labour in the process of modernization, money should become increasingly an instrument of distribution. The idea that money is a medium of exchange is related to the belief that all wealth is created by the current labour of the world, and Douglas clearly rejected this belief, stating that the cultural inheritance of society is the primary factor in the creation of wealth, which makes money a distribution mechanism, not a medium of exchange.

Douglas also claimed the problem of production, or scarcity

In economics, scarcity "refers to the basic fact of life that there exists only a finite amount of human and nonhuman resources which the best technical knowledge is capable of using to produce only limited maximum amounts of each economic good. ...

, had long been solved. The new problem was one of distribution. However, so long as orthodox economics makes scarcity a value, banks will continue to believe that they are creating value for the money they produce by making it scarce. Douglas criticized the banking system on two counts:

# for being a form of government which has been centralizing its power for centuries, and

# for claiming ownership of the money they create.

The former Douglas identified as being anti-social in policy. The latter he claimed was equivalent to claiming ownership of the nation. According to Douglas, money is merely an abstract representation of the real credit of the community, which is the ability of the community to deliver goods and services

Service may refer to:

Activities

* Administrative service, a required part of the workload of university faculty

* Civil service, the body of employees of a government

* Community service, volunteer service for the benefit of a community or a p ...

, when and where they are required.

The A + B theorem

In January 1919, "A Mechanical View of Economics" by C. H. Douglas was the first article to be published in the magazine ''New Age'', edited by

In January 1919, "A Mechanical View of Economics" by C. H. Douglas was the first article to be published in the magazine ''New Age'', edited by Alfred Richard Orage

Alfred Richard Orage (22 January 1873 – 6 November 1934) was a British influential figure in socialist politics and modernist culture, now best known for editing the magazine ''The New Age'' before the First World War. While he was working as a ...

, critiquing the methods by which economic activity is typically measured:

It is not the purpose of this short article to depreciate the services of accountants; in fact, under the existing conditions probably no body of men has done more to crystallise the data on which we carry on the business of the world; but the utter confusion of thought which has undoubtedly arisen from the calm assumption of the book-keeper and the accountant that he and he alone was in a position to assign positive or negative values to the quantities represented by his figures is one of the outstanding curiosities of the industrial system; and the attempt to mould the activities of a great empire on such a basis is surely the final condemnation of an out-worn method.In 1920, Douglas presented the A + B theorem in his book, ''Credit-Power and Democracy'', in critique of accounting methodology pertinent to income and prices. In the fourth, Australian Edition of 1933, Douglas states:

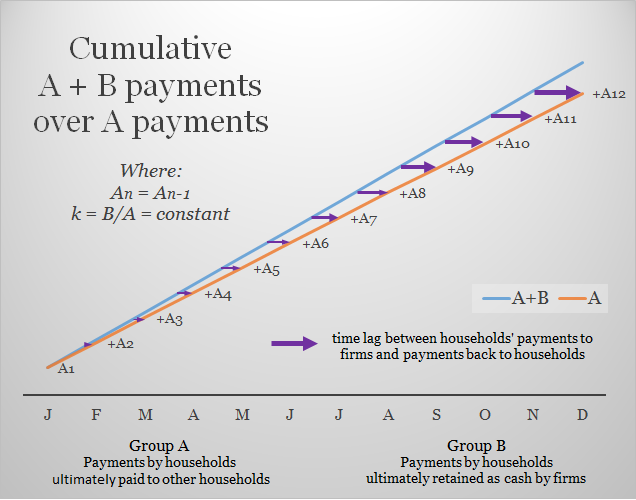

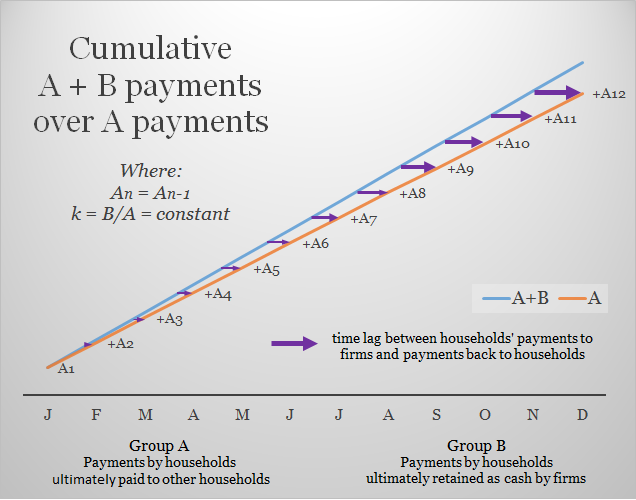

A factory or other productive organization has, besides its economic function as a producer of goods, a financial aspect – it may be regarded on the one hand as a device for the distribution of purchasing-power to individuals through the media of wages, salaries, and dividends; and on the other hand as a manufactory of prices – financial values. From this standpoint, its payments may be divided into two groups: :Group A: ''All payments made to individuals (wages, salaries, and dividends).'' :Group B: ''All payments made to other organizations (raw materials, bank charges, and other external costs).'' Now the rate of flow of purchasing-power to individuals is represented by A, but since all payments go into prices, the rate of flow of prices cannot be less than A+B. The product of any factory may be considered as something which the public ought to be able to buy, although in many cases it is an intermediate product of no use to individuals but only to a subsequent manufacture; but since A will not purchase A+B; a proportion of the product at least equivalent to B must be distributed by a form of purchasing-power which is not comprised in the description grouped under A. It will be necessary at a later stage to show that this additional purchasing power is provided by loan credit (bank overdrafts) or export credit.Beyond empirical evidence, Douglas claims this

deductive

Deductive reasoning is the mental process of drawing deductive inferences. An inference is deductively valid if its conclusion follows logically from its premises, i.e. if it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be fals ...

theorem

In mathematics, a theorem is a statement that has been proved, or can be proved. The ''proof'' of a theorem is a logical argument that uses the inference rules of a deductive system to establish that the theorem is a logical consequence of th ...

demonstrates that total prices increase faster than total incomes when regarded as a flow.

In his pamphlet entitled "The New and the Old Economics", Douglas describes the cause of "B" payments:

I think that a little consideration will make it clear that in this sense an overhead charge is any charge in respect of which the actual distributed purchasing power does not still exist, and that practically this means any charge created at a further distance in the past than the period of cyclic rate of circulation of money. There is no fundamental difference between tools and intermediate products, and the latter may therefore be included.In 1932, Douglas estimated the cyclic rate of circulation of money to be approximately three weeks. The cyclic rate of circulation of money measures the amount of time required for a loan to pass through the productive system and return to the bank. This can be calculated by determining the amount of clearings through the bank in a year divided by the average amount of

deposits

A deposit account is a bank account maintained by a financial institution in which a customer can deposit and withdraw money. Deposit accounts can be savings accounts, Transaction account#Current accounts, current accounts or any of several othe ...

held at the banks (which varies very little). The result is the number of times money must turnover in order to produce these clearing house

Clearing house or Clearinghouse may refer to:

Banking and finance

* Clearing house (finance)

* Automated clearing house

* ACH Network, an electronic network for financial transactions in the U.S.

* Bankers' clearing house

* Cheque clearing

* Cl ...

figures. In a testimony before the Alberta Agricultural Committee of the Alberta Legislature in 1934, Douglas said:

Now we know there are an increasing number of charges which originated from a period much anterior to three weeks, and included in those charges, as a matter of fact, are most of the charges made in, respect of purchases from one organization to another, but all such charges as capital charges (for instance, on a railway which was constructed a year, two years, three years, five or ten years ago, where charges are still extant), cannot be liquidated by a stream of purchasing power which does not increase in volume and which has a period of three weeks. The consequence is, you have a piling up of debt, you have in many cases a diminution of purchasing power being equivalent to the price of the goods for sale.According to Douglas, the major consequence of the problem he identified in his A+B theorem is exponentially increasing debt. Further, he believed that society is forced to produce goods that consumers either do not want or cannot afford to purchase. The latter represents a favorable

balance of trade

The balance of trade, commercial balance, or net exports (sometimes symbolized as NX), is the difference between the monetary value of a nation's exports and imports over a certain time period. Sometimes a distinction is made between a balance ...

, meaning a country exports more than it imports. But not every country can pursue this objective at the same time, as one country must import more than it exports when another country exports more than it imports. Douglas proposed that the long-term consequence of this policy is a trade war

A trade war is an economic conflict often resulting from extreme protectionism in which states raise or create tariffs or other trade barriers against each other in response to trade barriers created by the other party. If tariffs are the exclus ...

, typically resulting in real war – hence, the social credit admonition, "He who calls for Full-Employment calls for War!", expressed by the Social Credit Party of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

The Social Credit Party of Great Britain and Northern Ireland was a political party in the United Kingdom. It grew out of the Kibbo Kift, which was established in 1920 as a more craft-based alternative for youth to the Boy Scouts.Peter Barberis, J ...

, led by John Hargrave

John Gordon Hargrave (6 June 1894 – 21 November 1982), (woodcraft name 'White Fox'), was a prominent youth leader in Britain during the 1920s and 1930s, Head Man of the Kibbo Kift, described in his obituary as an 'author, cartoonist, inve ...

. The former represents excessive capital production and/or military build-up. Military buildup necessitates either the violent use of weapons or a superfluous accumulation of them. Douglas believed that excessive capital production is only a temporary correction, because the cost of the capital appears in the cost of consumer goods, or taxes, which will further exacerbate future gaps between income and prices.

In the first place, these capital goods have to be sold to someone. They form a reservoir of forced exports. They must, as intermediate products, enter somehow into the price of subsequent ultimate products and they produce a position of most unstable equilibrium, since the life of capital goods is in general longer than that of consumable goods, or ultimate products, and yet in order to meet the requirements for money to buy the consumable goods, the rate of production of capital goods must be continuously increased.

The A + B theorem and a cost accounting view of inflation

The replacement of labour by capital in the productive process implies that overhead charges (B) increase in relation to income (A), because "'B' is the financial representation of the lever of capital". As Douglas stated in his first article, "The Delusion of Superproduction":The factory cost – not the selling price – of any article under our present industrial and financial system is made up of three main divisions-direct labor cost, material cost and overhead charges, the ratio of which varies widely, with the "modernity" of the method of production. For instance, a sculptor producing a work of art with the aid of simple tools and a block of marble has next to no overhead charges, but a very low rate of production, while a modern screw-making plant using automatic machines may have very high overhead charges and very low direct labour cost, or high rates of production. Since increased industrial output per individual depends mainly on tools and method, it may almost be stated as a law that intensified production means a progressively higher ratio of overhead charges to direct labour cost, and, apart from artificial reasons, this is simply an indication of the extent to which machinery replaces manual labour, as it should.If overhead charges are constantly increasing relative to income, any attempt to stabilize or increase income results in increasing prices. If income is constant or increasing, and overhead charges are continuously increasing due to technological advancement, then prices, which equal income plus overhead charges, must also increase. Further, any attempt to stabilize or decrease prices must be met by decreasing incomes according to this analysis. As the

Phillips Curve

The Phillips curve is an economic model, named after William Phillips hypothesizing a correlation between reduction in unemployment and increased rates of wage rises within an economy. While Phillips himself did not state a linked relationship ...

demonstrates, inflation and unemployment are trade-offs, unless prices are reduced from monies derived from outside the productive system. According to Douglas's A+B theorem, the systemic problem of increasing prices, or inflation, is not "too much money chasing too few goods", but is the increasing rate of overhead charges in production due to the replacement of labour by capital in industry combined with a policy of full employment. Douglas did not suggest that inflation cannot be caused by too much money chasing too few consumer goods, but according to his analysis this is not the only cause of inflation, and inflation is systemic according to the rules of cost accountancy given overhead charges are constantly increasing relative to income. In other words, inflation can exist even if consumers have insufficient purchasing power to buy back all of production. Douglas claimed that there were two limits which governed prices, a lower limit governed by the cost of production, and an upper limit governed by what an article will fetch on the open market. Douglas suggested that this is the reason why deflation is regarded as a problem in orthodox economics because bankers and businessmen were very apt to forget the lower limit of prices.

Compensated price and national dividend

Douglas proposed to eliminate the gap between purchasing power and prices by increasing consumer purchasing power with credits which do not appear in prices in the form of a price rebate and a dividend. Formally called a "Compensated Price" and a "National (or Consumer) Dividend", a National Credit Office would be charged with the task of calculating the size of the rebate and dividend by determining a nationalbalance sheet

In financial accounting, a balance sheet (also known as statement of financial position or statement of financial condition) is a summary of the financial balances of an individual or organization, whether it be a sole proprietorship, a business ...

, and calculating aggregate production and consumption statistics.

The price rebate is based upon the observation that the real cost of production is the mean rate of consumption over the mean rate of production for an equivalent period of time.

:

where

* ''M'' = money distributed for a given programme of production,

* ''C'' = consumption,

* ''P'' = production.

The physical cost of producing something is the materials and capital that were consumed in its production, plus that amount of consumer goods labour consumed during its production. This total consumption represents the physical, or real, cost of production.

:

where

* Consumption = cost of consumer goods,

* Depreciation = depreciation of real capital,

* Credit = Credit Created,

* Production = cost of total production

Since fewer inputs are consumed to produce a unit of output with every improvement in process, the real cost of production falls over time. As a result, prices should also decrease with the progression of time. "As society's capacity to deliver goods and services is increased by the use of plant and still more by scientific progress, and decreased by the production, maintenance, or depreciation of it, we can issue credit, in costs, at a greater rate than the rate at which we take it back through prices of ultimate products, if capacity to supply individuals exceeds desire."

Based on his conclusion that the real cost of production is less than the financial cost of production, the Douglas price rebate (Compensated Price) is determined by the ratio of consumption to production. Since consumption over a period of time is typically less than production over the same period of time in any industrial society, the real cost of goods should be less than the financial cost.

For example, if the money cost of a good is $100, and the ratio of consumption to production is 3/4, then the real cost of the good is $100(3/4) = $75. As a result, if a consumer spent $100 for a good, the National Credit Authority would rebate the consumer $25. The good costs the consumer $75, the retailer receives $100, and the consumer receives the difference of $25 via new credits created by the National Credit Authority.

The National Dividend is justified by the displacement of labour in the productive process due to technological increases in productivity. As human labour is increasingly replaced by machines in the productive process, Douglas believed people should be free to consume while enjoying increasing amounts of leisure, and that the Dividend would provide this freedom

Freedom is understood as either having the ability to act or change without constraint or to possess the power and resources to fulfill one's purposes unhindered. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving on ...

.

Critics of the A + B theorem and rebuttal

Critics of the theorem, such as J. M. Pullen, Hawtrey and J. M. Keynes argue there is no difference between A and B payments. Other critics, such as Gary North, argue that social credit policies are inflationary. "The A + B theorem has met with almost universal rejection from academic economists on the grounds that, although B payments may be made initially to "other organizations," they will not necessarily be lost to the flow of available purchasing power. A and B payments overlap through time. Even if the B payments are received and spent before the finished product is available for purchase, current purchasing power will be boosted by B payments received in the current production of goods that will be available for purchase in the future." A. W. Joseph replied to this specific criticism in a paper given to the Birmingham Actuarial Society, "Banking and Industry":Let A1+B1 be the costs in a period to time of articles produced by factories making consumable goods divided up into A1 costs which refer to money paid to individuals by means of salaries, wages, dividends, etc., and B1 costs which refer to money paid to other institutions. Let A2, B2 be the corresponding costs of factories producing capital equipment. The money distributed to individuals is A1+A2 and the cost of the final consumable goods is A1+B1. If money in the hands of the public is to be equal to the costs of consumable articles produced then A1+A2 = A1+B1 and therefore A2=B1. Now modern science has brought us to the stage where machines are more and more taking the place of human labour in producing goods, i.e. A1 is becoming less important relatively to B1 and A2 less important relatively to B2.

In symbols if B1/A1 = k1 and B2/A2 = k2 both k1 and k2 are increasing.

Since A2=B1 this means that (A2+B2)/(A1+B1)= (1+k2)*A2/(1+1/k1)*B1 = (1+k2)/(1+1/k1) which is increasing.

Thus in order that the economic system should keep working it is essential that capital goods should be produced in ever increasing quantity relatively to consumable goods. As soon as the ratio of capital goods to consumable goods slackens, costs exceed money distributed, i.e. the consumer is unable to purchase the consumable goods coming on the market."And in a reply to Dr. Hobson, Douglas restated his central thesis: "To reiterate categorically, the theorem criticised by Mr. Hobson: the wages, salaries and dividends distributed during a given period do not, and cannot, buy the production of that period; that production can only be bought, i.e., distributed, under present conditions by a draft, and an increasing draft, on the purchasing power distributed in respect of future production, and this latter is mainly and increasingly derived from financial credit created by the banks." Incomes are paid to workers during a multi-stage program of production. According to the convention of accepted orthodox rules of accountancy, those incomes are part of the financial cost and price of the final product. For the product to be purchased with incomes earned in respect of its manufacture, all of these incomes would have to be saved until the product's completion. Douglas argued that incomes are typically spent on past production to meet the present needs of living, and will not be available to purchase goods completed in the future – goods which must include the sum of incomes paid out during their period of manufacture in their price. Consequently, this does not liquidate the financial cost of production inasmuch as it merely passes charges of one accountancy period on as mounting charges against future periods. In other words, according to Douglas, supply does not create enough demand to liquidate all the costs of production. Douglas denied the validity of

Say's Law

In classical economics, Say's law, or the law of markets, is the claim that the production of a product creates demand for another product by providing something of value which can be exchanged for that other product. So, production is the source ...

in economics.

While John Maynard Keynes referred to Douglas as a "private, perhaps, but not a major in the brave army of heretics", he did state that Douglas "is entitled to claim, as against some of his orthodox adversaries, that he at least has not been wholly oblivious of the outstanding problem of our economic system". While Keynes said that Douglas's A+B theorem "includes much mere mystification", he reaches a similar conclusion to Douglas when he states:

Thus the problem of providing that new capital-investment shall always outrun capital-disinvestment sufficiently to fill the gap between net income and consumption, presents a problem which is increasingly difficult as capital increases. New capital-investment can only take place in excess of current capital-disinvestment if future expenditure on consumption is expected to increase. Each time we secure to-day's equilibrium by increased investment we are aggravating the difficulty of securing equilibrium to-morrow.The criticism that social credit policies are inflationary is based upon what economists call the

quantity theory of money

In monetary economics, the quantity theory of money (often abbreviated QTM) is one of the directions of Western economic thought that emerged in the 16th-17th centuries. The QTM states that the general price level of goods and services is directly ...

, which states that the quantity of money multiplied by its velocity of circulation equals total purchasing power. Douglas was quite critical of this theory stating, "The velocity of the circulation of money in the ordinary sense of the phrase, is – if I may put it that way – a complete myth. No additional purchasing power at all is created by the velocity of the circulation of money. The rate of transfer from hand-to-hand, as you might say, of goods is increased, of course, by the rate of spending, but no more costs can be canceled by one unit of purchasing power than one unit of cost. Every time a unit of purchasing power passes through the costing system it creates a cost, and when it comes back again to the same costing system by the buying and transfer of the unit of production to the consuming system it may be cancelled, but that process is quite irrespective of what is called the velocity of money, so the categorical answer is that I do not take any account of the velocity of money in that sense." The Alberta Social Credit government published in a committee report what was perceived as an error in regards to this theory: "The fallacy in the theory lies in the incorrect assumption that money 'circulates', whereas it is issued against production, and withdrawn as purchasing power as the goods are bought for consumption."

Other critics argue that if the gap between income and prices exists as Douglas claimed, the economy would have collapsed in short order. They also argue that there are periods of time in which purchasing power is in excess of the price of consumer goods for sale.

Douglas replied to these criticisms in his testimony before the Alberta Agricultural Committee:

What people who say that forget is that we were piling up debt at that time at the rate of ten millions sterling a day and if it can be shown, and it can be shown, that we are increasing debt continuously by normal operation of the banking system and the financial system at the present time, then that is proof that we are not distributing purchasing power sufficient to buy the goods for sale at that time; otherwise we should not be increasing debt, and that is the situation.

Political theory

C.H. Douglas defined democracy as the "will of the people", not rule by the majority, suggesting that social credit could be implemented by any political party supported by effective public demand. Once implemented to achieve a realistic integration of means and ends, party politics would cease to exist. Traditional ballot box democracy is incompatible with Social Credit, which assumes the right of individuals to choose freely one choice at a time, and to contract out of unsatisfactory associations. Douglas advocated what he called the "responsible vote", where anonymity in the voting process would no longer exist. "The individual voter must be made individually responsible, not collectively taxable, for his vote." Douglas believed that party politics should be replaced by a "union of electors" in which the only role of an elected official would be to implement the popular will. Douglas believed that the implementation of such a system was necessary as otherwise the government would be controlled by international financiers. Douglas also opposed thesecret ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vote ...

arguing that it resulted in electoral irresponsibility, calling it a "Jewish" technique used to ensure Barabbas

Barabbas (; ) was, according to the New Testament, a prisoner who was chosen over Jesus by the crowd in Jerusalem to be pardoned and released by Roman governor Pontius Pilate at the Passover feast.

Biblical account

According to all four canoni ...

was freed leaving Christ to be crucified.

Douglas considered the constitution an organism, not an organization. In this view, establishing the supremacy of common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipresen ...

is essential to ensure protection of individual rights

Group rights, also known as collective rights, are rights held by a group '' qua'' a group rather than individually by its members; in contrast, individual rights are rights held by individual people; even if they are group-differentiated, which ...

from an all-powerful parliament. Douglas also believed the effectiveness of British government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_es ...

is determined structurally by application of a Christian concept known as Trinitarianism

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the ...

: "In some form or other, sovereignty in the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

for the last two thousand years has been Trinitarian. Whether we look on this Trinitarianism under the names of King, Lords and Commons or as Policy, Sanctions and Administration, the Trinity-in-Unity has existed, and our national success has been greatest when the balance (never perfect) has been approached."

Opposing the formation of Social Credit parties, C.H. Douglas believed a group of elected amateurs should never direct a group of competent experts in technical matters. While experts are ultimately responsible for achieving results, the goal of politicians should be to pressure those experts to deliver policy results desired by the populace. According to Douglas, "the proper function of Parliament is to force all activities of a public nature to be carried on so that the individuals who comprise the public may derive the maximum benefit from them. Once the idea is grasped, the criminal absurdity of the party system

A party system is a concept in comparative political science concerning the system of government by political parties in a democratic country. The idea is that political parties have basic similarities: they control the government, have a stab ...

becomes evident."

History

C. H. Douglas was a

C. H. Douglas was a civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing ...

who pursued his higher education at Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

. His early writings appeared most notably in the British intellectual journal ''The New Age

''The New Age'' was a British weekly magazine (1894–1938), inspired by Fabian socialism, and credited as a major influence on literature and the arts during its heyday from 1907 to 1922, when it was edited by Alfred Richard Orage. It publishe ...

''. The editor of that publication, Alfred Orage

Alfred Richard Orage (22 January 1873 – 6 November 1934) was a British people, British influential figure in socialist politics and modernist culture, now best known for editing the magazine ''The New Age'' before the First World War. While he ...

, devoted the magazines ''The New Age'' and later ''The New English Weekly'' to the promulgation of Douglas's ideas until his death on the eve of his BBC speech on social credit, 5 November 1934, in the ''Poverty in Plenty'' Series.

Douglas's first book, ''Economic Democracy'', was published in 1920, soon after his article ''The Delusion of Super-Production'' appeared in 1918 in the ''English Review''. Among Douglas's other early works were ''The Control and Distribution of Production'', ''Credit-Power and Democracy'', ''Warning Democracy'' and ''The Monopoly of Credit''. Of considerable interest is the evidence he presented to the Canadian House of Commons Select Committee on Banking and Commerce in 1923, to the British Parliamentary Macmillan Committee on Finance and Industry in 1930, which included exchanges with economist John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

, and to the Agricultural Committee of the Alberta Legislature

The Legislature of Alberta is the unicameral legislature of the province of Alberta, Canada. The legislature is made of two elements: the Lieutenant Governor of Alberta,. and the Legislative Assembly of Alberta. The legislature has existed s ...

in 1934 during the term of the United Farmers of Alberta

The United Farmers of Alberta (UFA) is an association of Alberta farmers that has served different roles in its 100-year history – as a lobby group, a successful political party, and as a farm-supply retail chain. As a political party, it forme ...

Government in that Canadian province

Within the geographical areas of Canada, the ten provinces and three territories are sub-national administrative divisions under the jurisdiction of the Canadian Constitution. In the 1867 Canadian Confederation, three provinces of British North ...

.

The writings of C. H. Douglas spawned a worldwide movement, most prominent in the British Commonwealth, with a presence in Europe and activities in the United States where Orage, during his sojourn there, promoted Douglas's ideas. In the United States, the New Democracy group was directed by the American author Gorham Munson Gorham Bockhaven Munson (May 26, 1896 – August 15, 1969) was an American literary critic.

Gorham was born in Amityville, New York to Hubert Barney Munson and Carrie Louise Morrow. He received his B.A. degree in 1917 from Wesleyan University, wh ...

who contributed a major book on social credit titled ''Aladdin’s Lamp: The Wealth of the American People''. While Canada and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

had electoral successes with "social credit" political parties, the efforts in England and Australia were devoted primarily to pressuring existing parties to implement social credit. This function was performed especially by Douglas's social credit secretariat in England and the Commonwealth Leagues of Rights in Australia. Douglas continued writing and contributing to the secretariat's journals, initially ''Social Credit'' and soon thereafter ''The Social Crediter'' (which continues to be published by the Secretariat) for the remainder of his lifetime, concentrating more on political and philosophical issues during his later years.

Origins

It was while he was reorganising the work at Farnborough, during World War I, that Douglas noticed that the weekly total costs of goods produced was greater than the sums paid to individuals forwage

A wage is payment made by an employer to an employee for work done in a specific period of time. Some examples of wage payments include compensatory payments such as ''minimum wage'', '' prevailing wage'', and ''yearly bonuses,'' and remune ...

s, salaries

A salary is a form of periodic payment from an employer to an employee, which may be specified in an employment contract. It is contrasted with piece wages, where each job, hour or other unit is paid separately, rather than on a periodic basis.

...

and dividend

A dividend is a distribution of profits by a corporation to its shareholders. When a corporation earns a profit or surplus, it is able to pay a portion of the profit as a dividend to shareholders. Any amount not distributed is taken to be re-in ...

s. This seemed to contradict the theory of classic Ricardian economics

Ricardian economics are the economic theories of David Ricardo, an English political economist born in 1772 who made a fortune as a stockbroker and loan broker.Henderson 826Fusfeld 325 At the age of 27, he read '' An Inquiry into the Nature and ...

, that all costs are distributed simultaneously as purchasing power

Purchasing power is the amount of goods and services that can be purchased with a unit of currency. For example, if one had taken one unit of currency to a store in the 1950s, it would have been possible to buy a greater number of items than would ...

. Troubled by the seeming difference between the way money flowed and the objectives of industry ("delivery of goods and services", in his opinion), Douglas decided to apply engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific method, scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad rang ...

methods to the economic system.

Douglas collected data from more than a hundred large British businesses and found that in nearly every case, except that of companies becoming bankrupt

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debt ...

, the sums paid out in salaries, wages and dividends were always less than the total costs of goods and services produced each week: consumer

A consumer is a person or a group who intends to order, or uses purchased goods, products, or services primarily for personal, social, family, household and similar needs, who is not directly related to entrepreneurial or business activities. T ...

s did not have enough income to buy back what they had made. He published his observations and conclusions in an article in the magazine ''The English Review

''The English Review'' was an English-language literary magazine published in London from 1908 to 1937. At its peak, the journal published some of the leading writers of its day.

History

The magazine was started by 1908 by Ford Madox Hueffer (la ...

'', where he suggested: "That we are living under a system of accountancy which renders the delivery of the nation's goods and services to itself a technical impossibility." He later formalized this observation in his A+B theorem. Douglas proposed to eliminate this difference between total prices and total incomes by augmenting consumers' purchasing power

Purchasing power is the amount of goods and services that can be purchased with a unit of currency. For example, if one had taken one unit of currency to a store in the 1950s, it would have been possible to buy a greater number of items than would ...

through a National Dividend and a Compensated Price Mechanism.

According to Douglas, the true purpose of production

Production may refer to:

Economics and business

* Production (economics)

* Production, the act of manufacturing goods

* Production, in the outline of industrial organization, the act of making products (goods and services)

* Production as a stati ...

is consumption

Consumption may refer to:

*Resource consumption

*Tuberculosis, an infectious disease, historically

* Consumption (ecology), receipt of energy by consuming other organisms

* Consumption (economics), the purchasing of newly produced goods for curren ...

, and production must serve the genuine, freely expressed interests of consumers. In order to accomplish this objective, he believed that each citizen should have a beneficial, not direct, inheritance in the communal capital conferred by complete access to consumer goods assured by the National Dividend and Compensated Price. Douglas thought that consumers, fully provided with adequate purchasing power

Purchasing power is the amount of goods and services that can be purchased with a unit of currency. For example, if one had taken one unit of currency to a store in the 1950s, it would have been possible to buy a greater number of items than would ...

, will establish the policy of production

Production may refer to:

Economics and business

* Production (economics)

* Production, the act of manufacturing goods

* Production, in the outline of industrial organization, the act of making products (goods and services)

* Production as a stati ...

through exercise of their monetary vote. In this view, the term economic democracy

Economic democracy is a socioeconomic philosophy that proposes to shift decision-making power from corporate managers and corporate shareholders to a larger group of public stakeholders that includes workers, customers, suppliers, neighbour ...

does not mean worker control of industry, but democratic control of credit. Removing the policy of production from banking institutions, government, and industry, social credit envisages an "aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At t ...

of producers, serving and accredited

Accreditation is the independent, third-party evaluation of a conformity assessment body (such as certification body, inspection body or laboratory) against recognised standards, conveying formal demonstration of its impartiality and competence to ...

by a democracy of consumers".

Political history

During early years of the philosophy, the management of the British Labour Party resisted pressure from some trade unionists to implement social credit, as hierarchical views ofFabian socialism

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. The Fa ...

, economic growth and full employment, were incompatible with the National Dividend and abolition of wage slavery

Wage slavery or slave wages refers to a person's dependence on wages (or a salary) for their livelihood, especially when wages are low, treatment and conditions are poor, and there are few chances of upward mobility.

The term is often us ...

suggested by Douglas. In an effort to discredit the social credit movement, one leading Fabian, Sidney Webb, is said to have declared that he did not care whether Douglas was technically correct or not – he simply did not like his policy.

Aberhart administration

In 1935, the world's firstSocial Credit

Social credit is a distributive philosophy of political economy developed by C. H. Douglas. Douglas attributed economic downturns to discrepancies between the cost of goods and the compensation of the workers who made them. To combat what he ...

government was elected in Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

, Canada led by William Aberhart

William Aberhart (December 30, 1878 – May 23, 1943), also known as "Bible Bill" for his outspoken Baptist views, was a Canadian politician and the seventh premier of Alberta from 1935 to his death in 1943. He was the founder and first leader ...

. A book by Maurice Colbourne, entitled ''The Meaning of Social Credit'', had convinced Aberhart that the theories of Major Douglas would facilitate for Alberta's recovery from the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. Aberhart added a heavy dose of fundamentalist Christianity

Christian fundamentalism, also known as fundamental Christianity or fundamentalist Christianity, is a religious movement emphasizing biblical literalism. In its modern form, it began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries among British and ...

to Douglas' theories, and the Canadian social credit movement

The Canadian social credit movement is a political movement originally based on the Social Credit theory of Major C. H. Douglas. Its supporters were colloquially known as Socreds in English and créditistes in French. It gained popularity and its ...

, which was largely nurtured in Alberta, thus acquired a strong social conservative

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and variety of conservatism which places emphasis on traditional power structures over social pluralism. Social conservatives organize in favor of duty, traditional values and social instituti ...

influence. However, some historians believe that neither Aberhart nor his supported understood the works of Douglas, and simply rallied around Aberhart's charisma.

Douglas was consulted by the 1921–1935 United Farmers of Alberta

The United Farmers of Alberta (UFA) is an association of Alberta farmers that has served different roles in its 100-year history – as a lobby group, a successful political party, and as a farm-supply retail chain. As a political party, it forme ...

provincial government in Alberta, but the UFA saw only difficulties in trying to bring in Social Credit. Douglas became an advisor to Aberhart, but withdrew after a short time and never visited Alberta after 1935 due to strategic differences. Aberhart sought orthodox counsel with respect to the Province's finances, and the correspondence between them was published by Douglas in his book, ''The Alberta Experiment''.

While Aberhart, the Premier, wanted to balance the provincial budget, Douglas argued the concept of a " balanced budget" was inconsistent with Social Credit principles. Douglas stated that, under existing rules of financial cost accountancy, balancing all budgets within an economy simultaneously is an arithmetic impossibility. In a letter to Aberhart, Douglas stated:

This seems to be a suitable occasion on which to emphasise the proposition that a Balanced Budget is quite inconsistent with the use of Social Credit (i.e., Real Credit – the ability to deliver goods and services 'as, when and where required') in the modern world, and is simply a statement in accounting figures that the progress of the country is stationary, i.e., that it consumes exactly what it produces, includingDouglas sent two social credit technical advisors from the United Kingdom, L. Denis Byrne and George F. Powell, to Alberta. But early attempts to pass social credit legislation were ruled by thecapital asset A capital asset is defined as property of any kind held by an assessee, whether connected with their business or profession or not connected with their business or profession. It includes all kinds of property, movable or immovable, tangible or i ...s. The result of the acceptance of this proposition is that allcapital appreciation Capital appreciation is an increase in the price or value of assets. It may refer to appreciation of company stocks or bonds held by an investor, an increase in land valuation, or other upward revaluation of fixed assets. Capital appreciation m ...becomes quite automatically the property of those who create and issue of money .e., the banking systemand the necessary unbalancing of the Budget is covered by Debts.

Supreme Court of Canada

The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC; french: Cour suprême du Canada, CSC) is the Supreme court, highest court in the Court system of Canada, judicial system of Canada. It comprises List of Justices of the Supreme Court of Canada, nine justices, wh ...

and/or the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

in London. Drawing on the monetary theories of Silvio Gesell, William Aberhart issued a currency substitute known as prosperity certificates. These scrip

A scrip (or ''chit'' in India) is any substitute for legal tender. It is often a form of credit. Scrips have been created and used for a variety of reasons, including exploitive payment of employees under truck systems; or for use in local comme ...

s intentionally depreciated in value the longer they were held, and Douglas openly criticized the idea:

Gesell's theory was that the trouble with the world was that people saved money so that what you had to do was to make them spend it faster. Disappearing money is the heaviest form of continuous taxation ever devised. The theory behind this idea of Gesell's was that what is required is to stimulate trade – that you have to get people frantically buying goods – a perfectly sound idea so long as the objective of life is merely trading.They did provide spending power to many impoverished Albertans in the time they were in circulation. Aberhart did bring in a measure of social credit, with the establishment of a government-owned banking system, the

Alberta Treasury Branches

ATB Financial is a financial institution and Crown corporation wholly owned by the province of Alberta, the only province in Canada with such a financial institution under its exclusive ownership.

Originally established as Alberta Treasury B ...

, still in operation today and now among the very few government-owned banks in North America that serve the public. (See for comparison Bank of North Dakota, the Bank of North Dakota.)

In 1938, Aberhart's Alberta Social Credit Party had 41,000 paid members, forming a broad coalition ranging from those who believed in Douglas' monetary policies to moderate Socialism, socialists. The latter group helped influence the party to form alliances with the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation and various Communism, communist groups in various local and provincial elections. However, as it became apparent that the party was failing to deliver on its promises to control prices and distribute Social dividend, social dividends, the party's membership fell rapidly, totaling just 3,500 by 1942.

Later activities

Under Ernest Manning, who succeeded Aberhart after his death in 1943, theAlberta Social Credit Party

Alberta Social Credit was a provincial political party in Alberta, Canada, that was founded on social credit monetary policy put forward by Clifford Hugh Douglas and on conservative Christian social values. The Canadian social credit movement w ...

saw a major revival, with a post-war economic boom and high oil revenues helping the party retain power for a quarter of a century. However, the party soon departed from its origins and became popularly identified as a right-wing politics, right wing populism, populist party, focusing much of its efforts on combatting Alberta's unions, and implementing a Red Scare, red scare. In the Secretariat's journal, ''An Act for the Better Management of the Credit of Alberta'', Douglas published a critical analysis of the Social Credit movement in Alberta, in which he said, "The Manning administration is no more a Social Credit administration than the British government is Labour". Manning accused Douglas and his followers of anti-Semitism, and purged "Douglasites" from the Alberta government. The British Columbia Social Credit Party won power in 1952 in the province to Alberta's west, but had little in common with Social Credit bank reform, Major Douglas or his theories.

Social credit parties also enjoyed some electoral success at the federal level in Canada. The Social Credit Party of Canada was initiated mostly by Albertans, and eventually created another base of support in Quebec. Social Credit also did well nationally in Social Credit Party (New Zealand), New Zealand, where it was the country's third party for almost 30 years.

Philosophy

Douglas described Social Credit as "the policy of a philosophy", and warned against considering it solely as a scheme for monetary reform. He called this philosophy "practical Christianity" and stated that its central issue is the Incarnation (Christianity), Incarnation. Douglas believed that there was a Biblical Canon, Canon which permeated the universe, and Jesus Christ was the Incarnation of this Canon. However, he also believed that Christianity remained ineffective so long as it remained Transcendentalism, transcendental. Religion, which derives from the Latin word (to "bind back"), was intended to be a binding back to reality. Social Credit is concerned with the incarnation of Christian principles in our organic affairs. Specifically, it is concerned with the principles of association and how to maximize the increments of association which redound to satisfaction of the individual in society – while minimizing any decrements of association. The goal of Social Credit is to maximize Immanence, immanent sovereignty. Social credit is consonant with the Christian doctrine of salvation through Grace (Christianity), unearned grace, and is therefore incompatible with any variant of the doctrine of salvation through works. Works need not be of Purity in intent or of desirable consequence and in themselves alone are as "filthy rags". For instance, the present system makes destructive, obscenely wasteful wars a virtual certainty – which provides much "work" for everyone. Social credit has been called the Third Alternative to the futile Left-right politics, Left-Right Duality. Although Douglas defined social credit as a philosophy with Christian origins, he did not envision a Christian theocracy. Douglas did not believe that religion should be mandated by law or external compulsion. Practical Christian society is Trinitarian in structure, based upon a constitution where the constitution is an organism changing in relation to our knowledge of the nature of the universe. "The progress of human society is best measured by the extent of its creative ability. Imbued with a number of natural gifts, notably reason, memory, understanding and free will, man has learned gradually to master the secrets of nature, and to build for himself a world wherein lie the potentialities of peace, security, liberty and abundance." Douglas said that social crediters want to build a new civilization based upon absolute economic security for the individual – where "they shall sit every man under his vine and under hisfig tree

''Ficus'' ( or ) is a genus of about 850 species of woody trees, shrubs, vines, epiphytes and hemiepiphytes in the family Moraceae. Collectively known as fig trees or figs, they are native throughout the tropics with a few species extending ...

; and none shall make them afraid." In keeping with this goal, Douglas was opposed to all forms of taxation on real property. This set social credit at variance from the land-taxing recommendations of Henry George.

Social credit society recognizes the fact that the relationship between man and God is unique. In this view, it is essential to allow man the greatest possible freedom in order to pursue this relationship. Douglas defined freedom as the ability to choose and refuse one choice at a time, and to contract out of unsatisfactory associations. Douglas believed that if people were given the economic security and leisure achievable in the context of a social credit dispensation, most would end their service to Mammon and use their free time to pursue spiritual, intellectual or cultural goals resulting in self-development. Douglas opposed what he termed "the pyramid of power". Totalitarianism represents this pyramid and is the antithesis of social credit. It turns the government into an end instead of a means, and the individual into a means instead of an end – – "the Devil is God upside down." Social credit is designed to give the individual the maximum freedom allowable given the need for association in economic, political and social matters. Social Credit elevates the importance of the individual and holds that all institutions exist to serve the individual – that the State exists to serve its citizens, not that individuals exist to serve the State.

Douglas emphasized that all policy derives from its respective philosophy and that "Society is primarily Metaphysics, metaphysical, and must have regard to the organic relationships of its prototype."C.H. Douglas letter to L.D. Byrne, 28 March 1940 Social credit rejects Dialectical Materialism, dialectical materialistic philosophy. "The tendency to argue from the particular to the general is a special case of the sequence from materialism to collectivism. If the universe is reduced to molecules, ultimately we can dispense with a catalogue and a dictionary; all things are the same thing, and all words are just sounds – molecules in motion."

Douglas divided philosophy into two schools of thought that he termed the "classical school" and the "modern school", which are broadly represented by philosophies of Aristotle and Francis Bacon respectively. Douglas was critical of both schools of thought, but believed that "the truth lies in appreciation of the fact that neither conception is useful without the other".

Criticism for antisemitism

Social crediters and Douglas have been criticized for spreading antisemitism. Douglas was critical of "international Jewry", especially in his later writings. He asserted that such Jews controlled many of the major banks and were involved in an Jewish conspiracy, international conspiracy to centralize the power of finance. Some people have claimed that Douglas was antisemitic because he was quite critical of pre-Christian philosophy. In his book ''Social Credit'', he wrote that, "It is not too much to say that one of the root ideas through which Christianity comes into conflict with the conceptions of the Old Testament and the ideals of the pre-Christians' era is in respect of this dethronement of abstractionism." Douglas was opposed to abstractionist philosophies because he believed that these philosophies inevitably resulted in the elevation of abstractions, such as the state, and legal fictions, such as corporate personhood, over the individual. He also believed that what Jews considered as abstractionist thought tended to encourage them to endorse communist ideals and an emphasis on collectives over individuals. Historian John L. Finlay, in his book ''Social Credit: The English Origins'', wrote, "Anti-Semitism of the Douglas kind, if it can be called anti-Semitism at all, may be fantastic, may be dangerous even, in that it may be twisted into a dreadful form, but it is not itself vicious nor evil." In his 1972 book, ''Social Credit: The English Origins'', Finlay argues that, "It must also be noted that while Douglas was critical of some aspects of Jewish thought, Douglas did not seek to discriminate against Jews as a people or race. It was never suggested that the National Dividend be withheld from them."Groups influenced by social credit

Australia

* Australian League of Rights * Douglas Credit PartyCanada

Federal political parties * Social Credit Party of Canada/Canadian social credit movement